Money and psychology are interwoven incredibly tight. So tight they’re hard to distinguish - so I just refer to them together as Money Psychology. It’s extremely misguided to think success with personal finances comes from an obsession with spreadsheets and quarterly statements. Sure those might be components, but without the right Money Psychology, those spreadsheets are worthless.

This is precisely why Morgan Housel and Ramit Sethi (their books are linked) are my two favorite personal finance thinkers and writers. As a self-proclaimed psychology nerd, their work fascinates me.

Ramit came out with a Podcast recently I’ve really been enjoying.

If I were to ask you the single most important influence on how you feel about money, what would you say? Because there is one that seems to trump all else that never gets talked about.

It doesn’t matter how much you make. It doesn’t matter how much you’ve saved. It definitely doesn’t matter where interest rates are. The thing that most influences how you feel about money is how you grew up around money (and your money experiences in general).

Ramit sits down with a couple in every episode where one or both partners feel anxious about money. The kicker is that in most situations, these people make a nice living. Each story is a little different, but it seems like they all have one thing in common. They faced financial hardships as a child. Or, their money psychology is shaped by the stock market they grew up in.

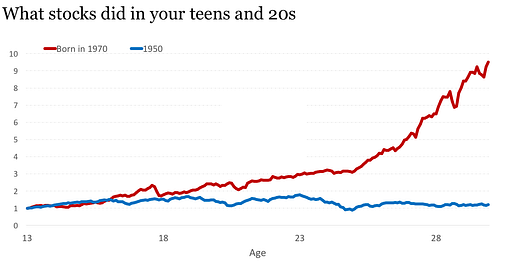

If you were born in 1970 the stock market went up 10-fold adjusted for inflation in your teens and 20s – your young impressionable years when you were learning baseline knowledge about how investing and the economy work. If you were born in 1950, the same market went exactly nowhere in your teens and 20s:

As Morgan Housel says: Your personal experiences make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world but maybe 80% of how you think the world works.

Or look at this forum - I’m 70 years old and I can’t spend my savings.

He says, “I can’t spend money without feelings of anxiety. It’s really painful.”

And here’s the kicker:

“I have $6 million in investments and a $1 million mortgage-free house. No debt. $60,000/year in social security (starting right now) and $25,000/year in income from my part-time job as a lawyer (mostly as arbitrator, work from home)”

But as you read further along, you see this:

“I think I know where this comes from - my father (a big influence on me) was born in 1920. His father died in 1932 (think about it ....). My father was extremely frugal, and he never invested a single penny in the stock market. Growing up in the 1920/1930s he distrusted it 100% for the rest of his life.”

A team of economists once crunched the data on a century’s worth of people’s investing habits and concluded: “Current [investment] beliefs depend on the realizations experienced in the past.”

Keep that quote in mind when debating people’s investing views. Or when you’re confused about their desire to hoard or blow money, their fear or greed in certain situations, or whenever else you can’t understand why people do what they do with money.

Things will make more sense.

Our money psychology is made up of a complicated mix of all things past and some present. All of us have a history with money. We grow up with too little or too much — or fall under the sway of parents or others who influence our attitude about saving and spending. As we age, money often becomes an indicator of our emotional well-being.

It’s fine to think about money frequently, enjoying its benefits and squeezing value from it. But it’s not healthy to fret about it constantly and let the “I-don’t-have-enough” worry eat away at you.

There have been thousands of personal finance articles written on how to spend money. Some of these articles emphasize frugality and reducing your expenses, while others focus on growing your income so you don’t have to worry about expenses at all. But, the problem with many of these approaches is that they are based upon one thing—guilt.

Between Suzie Orman telling you that buying coffee is equivalent to “peeing away $1 million” and Gary Vaynerchuk asking you whether you are working hard enough, mainstream financial advice is built upon sowing doubt around your decision-making. Should you buy that car? How about those fancy clothes? What about a daily latte? All guilt-driven.

This kind of advice forces you to constantly second guess yourself and creates anxiety around spending money. And having more money doesn’t necessarily solve this problem either. A 2017 survey by Spectrem Group found that 20% of investors worth between $5 million and $25 million were concerned about having enough money to make it through retirement.

But this is no way to live your life. Yes, money is important, but it shouldn’t alarm you anytime you see a price tag. If you have ever debated whether you could afford something even when you had sufficient funds, then the problem isn’t you, but the framework that you are using to think about your spending.

The best framework I’ve seen is the “The 2x Rule.” The 2x Rule works like this: Anytime you want to splurge on something, you have to take the same amount of money and invest it as well.

So if you wanted to buy a $400 pair of shoes, you’d also have to buy $400 worth of equities. This makes you re-evaluate how much you really want something because if you’re not willing to save 2x for it, then maybe it’s not that important to you to begin with.

I like this rule because it removes the psychological guilt associated with binge purchases. And you don’t have to invest the money for The 2x Rule to work effectively either. For example, you could donate the other half to a charity and have the same guilt-free effect. Every “extravagant” dollar you spend on yourself could be matched with a “charity” dollar that goes to a worthy cause. Not only does this allow you to help others, but you won’t feel bad when you spoil yourself.